The Character

Margaretha Gertruida Zelle – Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

Margaretha Gertruida Zelle – Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

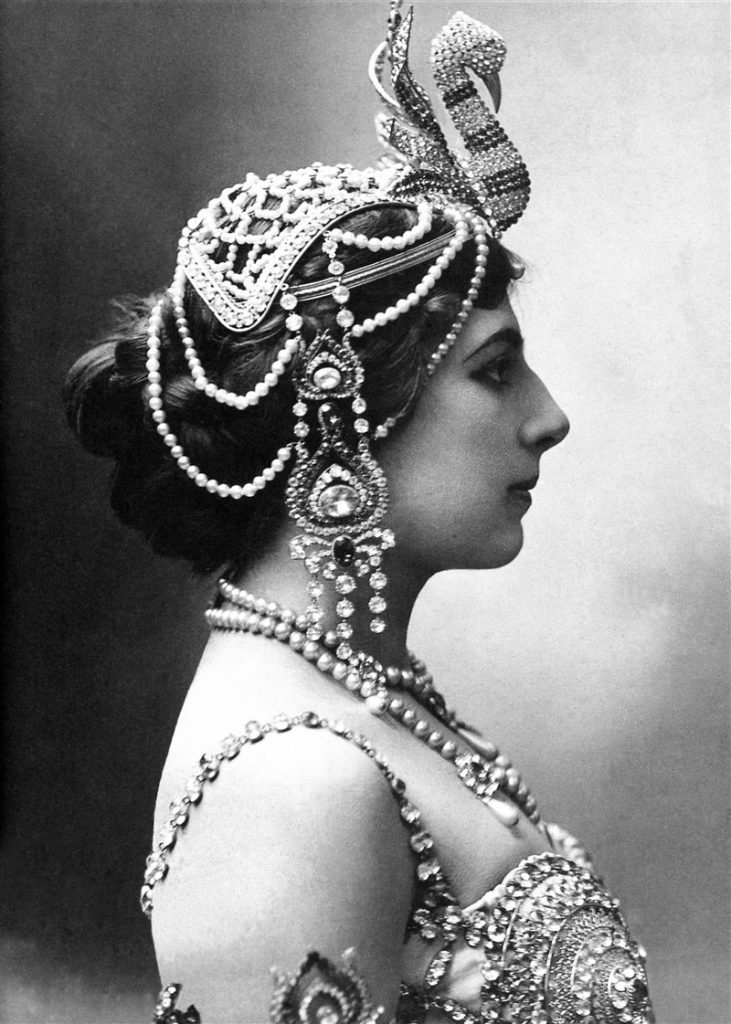

Mata Hari, 1906 – Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

Mata Hari performing at the Musée Guimet in Paris, 1905 – Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

Mata Hari – Photo Cordon Press / Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

Mata Hari on the day of her arrest – Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

Arrest photo of Margaretha Zelle – Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

The real Mata Hari

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle was born in the city of Leeuwarden, province of Friesland, the Netherlands, on August 7, 1876.

She was the eldest and only woman of four children from the marriage of Adam Zelle (1840-1910) and Antje van der Meulen (1842-1891). Her parents divorced and her mother passed away a few years after the divorce. Her father remarried Susanna Catharina ten Hoove (1844-1913).

At the age of 16, after the death of her mother, she Margaretha went to live in Den Haag with her uncle, due to the harassment she suffered from one of the directors of the school where she was educated to become a teacher.

In 1895, she responds to an advertisement from Captain Rudolf MacLeod (1856-1928), a military man 20 years her senior, who was requesting a wife for her before traveling to the East Indies. After a few months of correspondence and a few dates, they were married in Amsterdam on July 11, 1895; she was then 18 years old.

They moved as a married couple to Java, and had two children: Norman-John, born on January 30, 1897, and Louise Jeanne (called Non), born on May 2, 1898. In 1899 the children fell ill and Norman-John died. . The first hypothesis was that he had died due to complications from the treatment of syphilis spread by his father to the whole family, but later it was discovered that both children had been poisoned in revenge against McLeod for his mistreatment of a servant and/or for the rape of a servant’s daughter. The death of the son was a severe blow to a marriage that was not working anyway. McLeod became an alcoholic and she, Margaretha, sought refuge in becoming interested in Javanese culture and Balinese folk dances, which would later serve her to gain fame and money, although she did not know it at that time.

The couple return to the Netherlands and legally separate on August 30, 1902. Mc Leod gains custody of Non.

Margaretha, alone, takes refuge first in the house of relatives in Nijmegen (The Netherlands) and then travels to Paris in 1903, trying a new path for her life.

Taking advantage of her knowledge of oriental culture and dance, Margaretha poses as an alleged princess of Java, under the name of Mata Hari, which in Malay means “the dawn’s eye”, and debuts at the Guimet Museum, owned by the collector Émile Étienne Guimet on March 13, 1905.

Mata Hari offered a show integrating the sacred oriental dances that she claimed to have learned since her childhood, and she used translucent fabrics from which she was stripped until she was dressed only in a mesh of the same color as her skin. She gave the illusion that she was almost completely naked, which was the main attraction of her number, although she never showed her breasts.

With the brahmanical and oriental dances she triumphed throughout Europe.

In 1906, her divorce trial takes place and McLeod definitively removes Margaretha from custody of her daughter, accusing her of misconduct, due to her artistic performance.

The fame of her performances and the mystery that she manages to create around them, makes her interact with many members of high society, politicians and high-level military officials, maintaining intimate relationships or romances with some of them.

During World War I, the Netherlands remained neutral, allowing Margaretha, as a Dutch citizen, to cross national borders freely, but her contacts and relationships with the military and even royalty gradually make her suspicious and she begins to be watched. Margaretha becomes involved in a romantic-sexual relationship with a Russian pilot in the service of the French army, Captain Vadim Maslov, whom she calls in her letters “the man I loved the most.”

In the summer of 1916, Captain Maslov was seriously injured and lost his left eye. Margaretha then asked permission to visit her wounded lover in the field hospital in Vittel, near the front. She was then met by agents from the Deuxième Bureau who told her that she would be allowed to travel to see Maslov if she agreed to spy for France. She had performed as Mata Hari several times before Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia. The Deuxième Bureau believed that she could gain information by seducing the Crown Prince for military secrets. Margaretha’s contact with the Deuxième Bureau was Captain Georges Ladoux, who would later become one of her main accusers.

In November 1916, she was traveling by steamer from Spain when her ship reached the British port of Falmouth and there she was arrested and taken to London, for questioning by Sir Basil Thomson, assistant commissioner at Scotland Yard in charge. of counter espionage. Initially detained at the Cannon Street police station, she was released as it was understood she had been mistaken for a Spanish spy, and she stayed at the Savoy Hotel.

This mishap makes her return to Madrid, where Margaretha meets with the German military attaché, Major Arnold Kalle, who sent a radio-telegram to Berlin, where Elsbeth Schragmüller, known at the time as Fräulein Doktor, was the Head of the Espionage Department. against France, in the Intelligence Service of the Supreme Command of the German Army. The radio-telegram informed him of the German agent H21, who was going to Paris and extracting $5,000 in payment for his services from the Bank Comptoir d’Escompte. The coincidence of her return to Paris together with the arrival of the transfer of bank funds, despite the fact that she could not withdraw the money from the bank, and in reality it was the payment of the services that she had rendered to France itself ; in addition to the telegram, encrypted in a code that the Germans knew was obsolete and easily decipherable by the French from the radio antenna on the Eiffel Tower, they directly indicted Mata Hari before the Deuxième Bureau, which suggests that the messages were devised with the firm intention of exposing Margaretha to the French.

On February 13, 1917, Margaretha was arrested in her room at the Hotel Elysée Palace on the Champs-Elysées in Paris. She was tried behind closed doors before a Court Martial on July 24, accused of spying for Germany and consequently causing the death of at least 50,000 soldiers, for which she was sentenced to death for high treason. Although French and British intelligence suspected her of spying for Germany, neither managed to produce conclusive evidence against her.

Margaretha’s main interrogator was Captain Pierre Bouchardon. She confessed to Bouchardon that she had accepted 20,000 francs from a German diplomat in the Netherlands to spy on France, in a time of financial need when she wanted to return to Paris, but insisted that she only passed on trivial information to the Germans since his loyalty was absolute to his adopted nation. Meanwhile, Ladoux had been building the case against his former agent by presenting all of his activities in the worst light possible, even going so far as to get involved in tampering with evidence.

In the spring of 1917, France was severely shaken by the Great Mutins of the French Army following the failure of the Nivelle offensive. Many believed that France could collapse simply as a result of war exhaustion. In July 1917, a new government under Georges Clemenceau had come to power with the promise of winning the war. In this context, having a German spy to blame for everything that had gone wrong in the war so far was in the best interest of the French government, making Mata Hari the perfect scapegoat, which explains why the case against him received maximum publicity in the French press.

Margaretha wrote several letters to the Dutch ambassador in Paris, claiming her innocence. “My international connections are due to my work as a dancer, nothing else… Because I didn’t really spy, it’s terrible that I can’t stand up for myself.” The most heartbreaking moment for Mata Hari during the trial occurred when her lover, Ella Maslov, declined to testify for her.

Bouchardon used the very fact that Margaretha was a woman as evidence of her guilt, stating: “Unscrupulous, accustomed to making use of men, she is the kind of woman who was born to be a spy.”

Margaretha was executed by a firing squad of 12 French soldiers at dawn on October 15, 1917, near the Château de Vincennes. She was 41 years old. According to an eyewitness account by British journalist Henry Wales, she refused to wear her blindfold as she was tied to the post.

Mata Hari’s body was not claimed by any member of the family and was consequently used for medical studies. Her head was embalmed and kept in the Museum of Anatomy in Paris. In 2000, archivists discovered that she had disappeared, possibly as early as 1958, according to curator Roger Saban, when the museum had been relocated. To this day she is still missing.

The year after Mata Hari’s execution, Captain Georges Ladoux was accused and arrested on the charge of “double agent”, although no evidence was found against him, for which he was acquitted.

Mata Hari’s sealed trial and other related documents, a total of 1,275 pages, were declassified by the French military in 2017, one hundred years after his execution. No evidence was found that Mata Hari had revealed any war secrets or passed on any sensitive information.

“I don’t know

if I will be remembered in the future,

but if so,

let no one see me as a victim

but as someone

who never stopped

fighting bravely

and paid the price she had to pay.”

Mata Hari

Films references:

(in case you want to know more about Mata Hari and different views of the character)

Mata Hari – Fries Museum Leeuwarden Collection

1920 – MATA HARI – Actress: Asta Nielsen – Directed by Ludwig Wolff

1931 – MATA HARI – Actress: Greta Garbo – Directed by George Fitzmaurice

1931 – DISHONORED – Actress: Marlene Dietrich – Directed by Josef von Sternberg

1964 – MATA HARI: AGENT H21 – Actress: Jeanne Moreau – Directed by Jean-Louis Richard

1981 – MATA HARI – Actress: Josine van Dalsum – Directed by John van de Rest

1985 – MATA HARI – Actress: Sylvia Kristel – Directed by Curtis Harrington

2016 – TANZ MIT DEM TOD – Actress: Natalia Wörner – Directed by Kai Christiansen

2017 – MATA HARI (tv serie) – Actress: Vahina Giocante – Directed by Dennis Berry